Campo de Cahuenga / Universal City Metro Station, Los Angeles CA.

The Trees of Queen Califa, 2000

Los Angeles Metro writes…

“Adjacent to the historic site of the Campo de Cahuenga, where in 1847 relinquished control of California to the United States, this station, designed by artist Margaret Garcia and architect Kate Diamond, focuses on the significance of this event to California history.

California was named by the Spaniards after the mythological black Amazon queen Califas who was said to have ruled a tribe of women warriors. Visitors descending into the station are greeted with a historic timeline highlighting key dates and events related to the area’s past. A series of highly stylized trees on the station platform provide a dynamic canopy over the interior space. Symbolizing life, time and growth, the design of these interior trees was influenced by mature pepper trees that once lined Lankershim Boulevard.

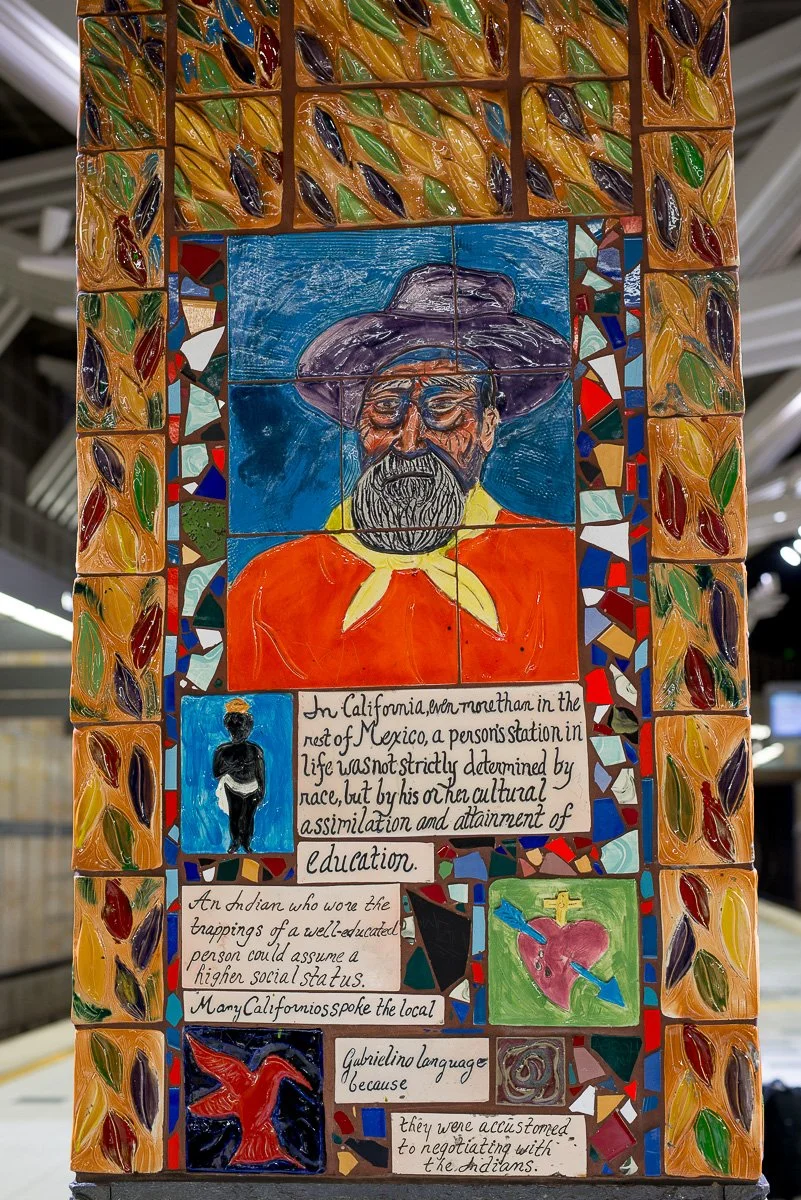

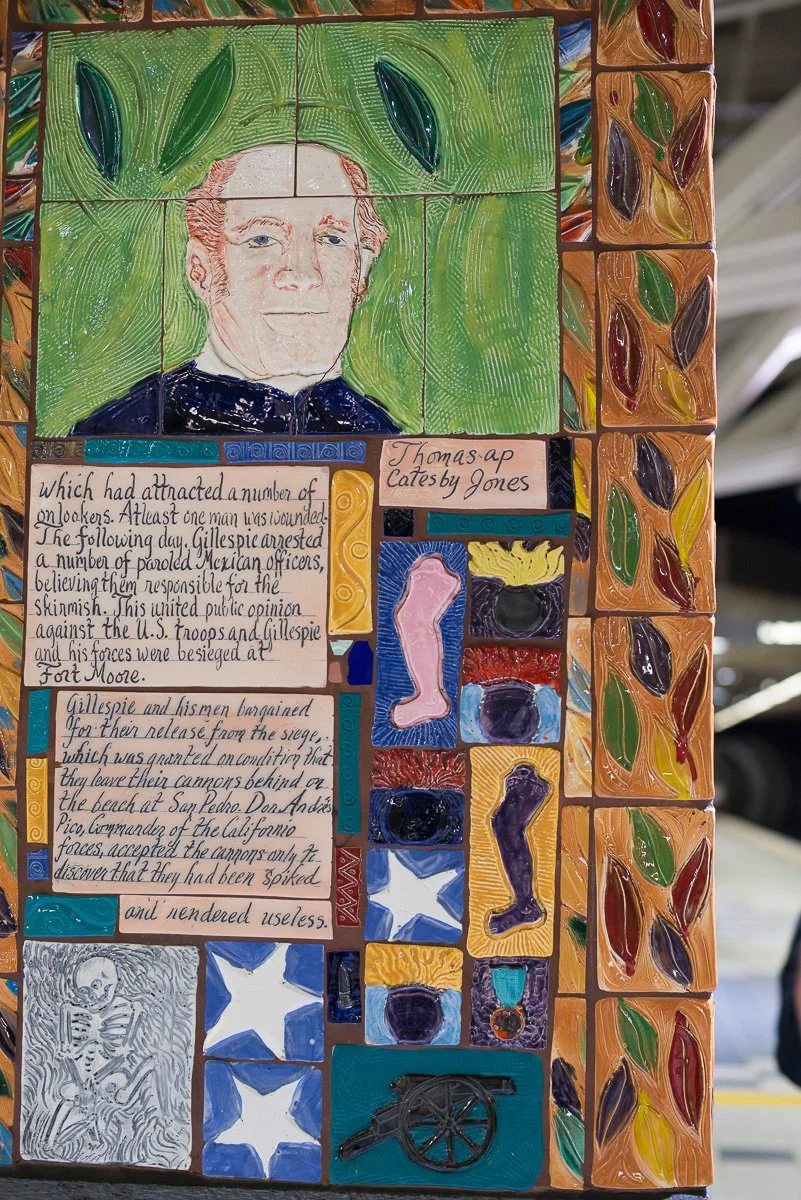

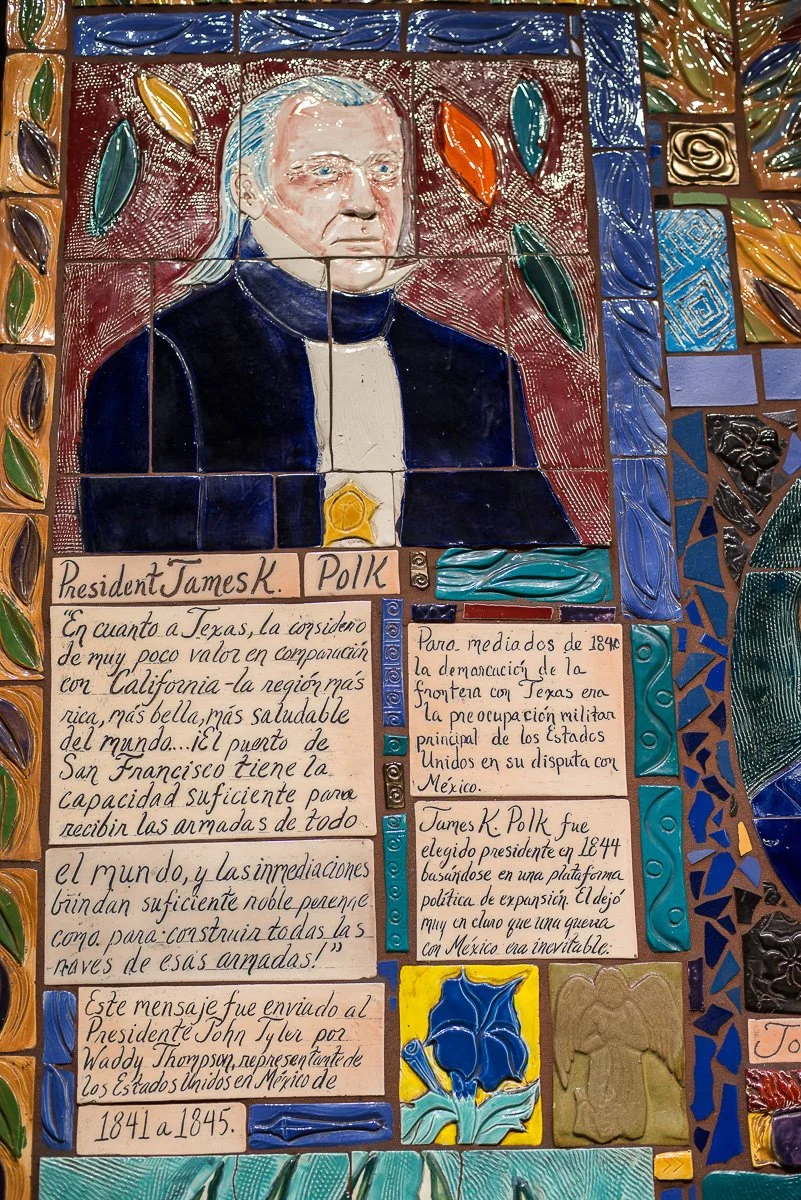

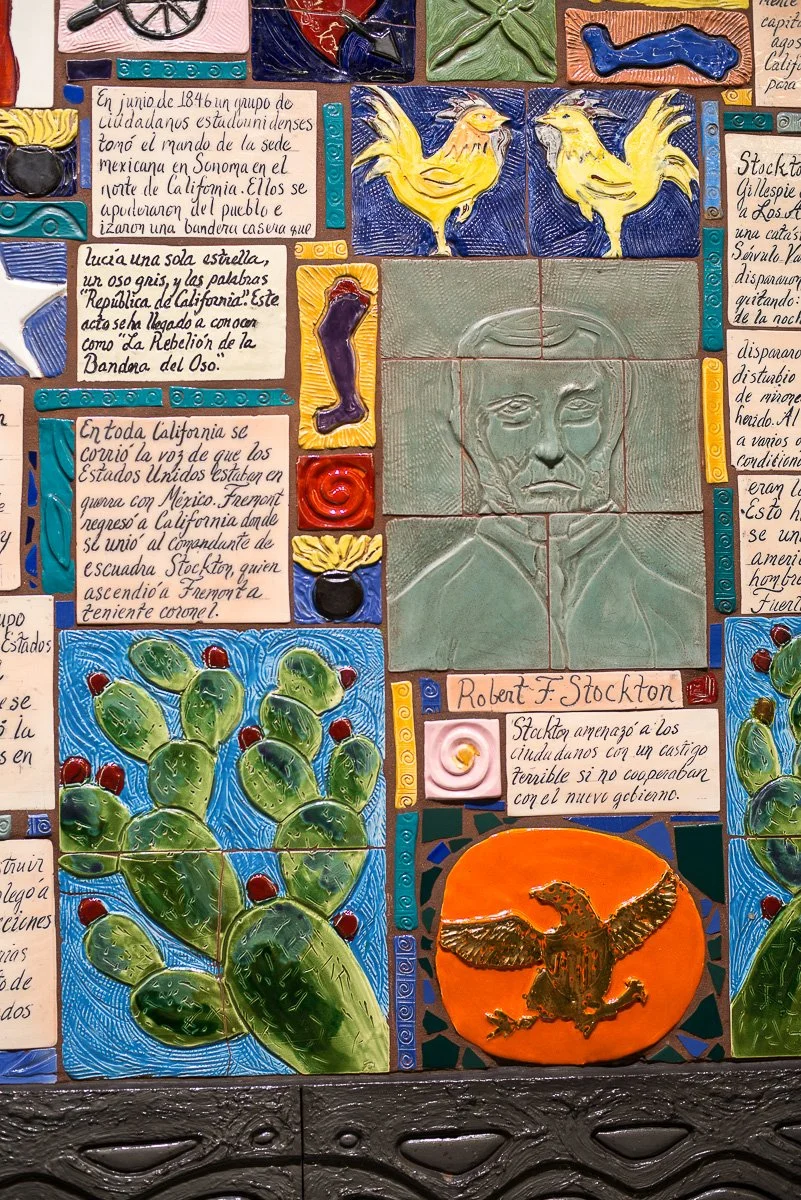

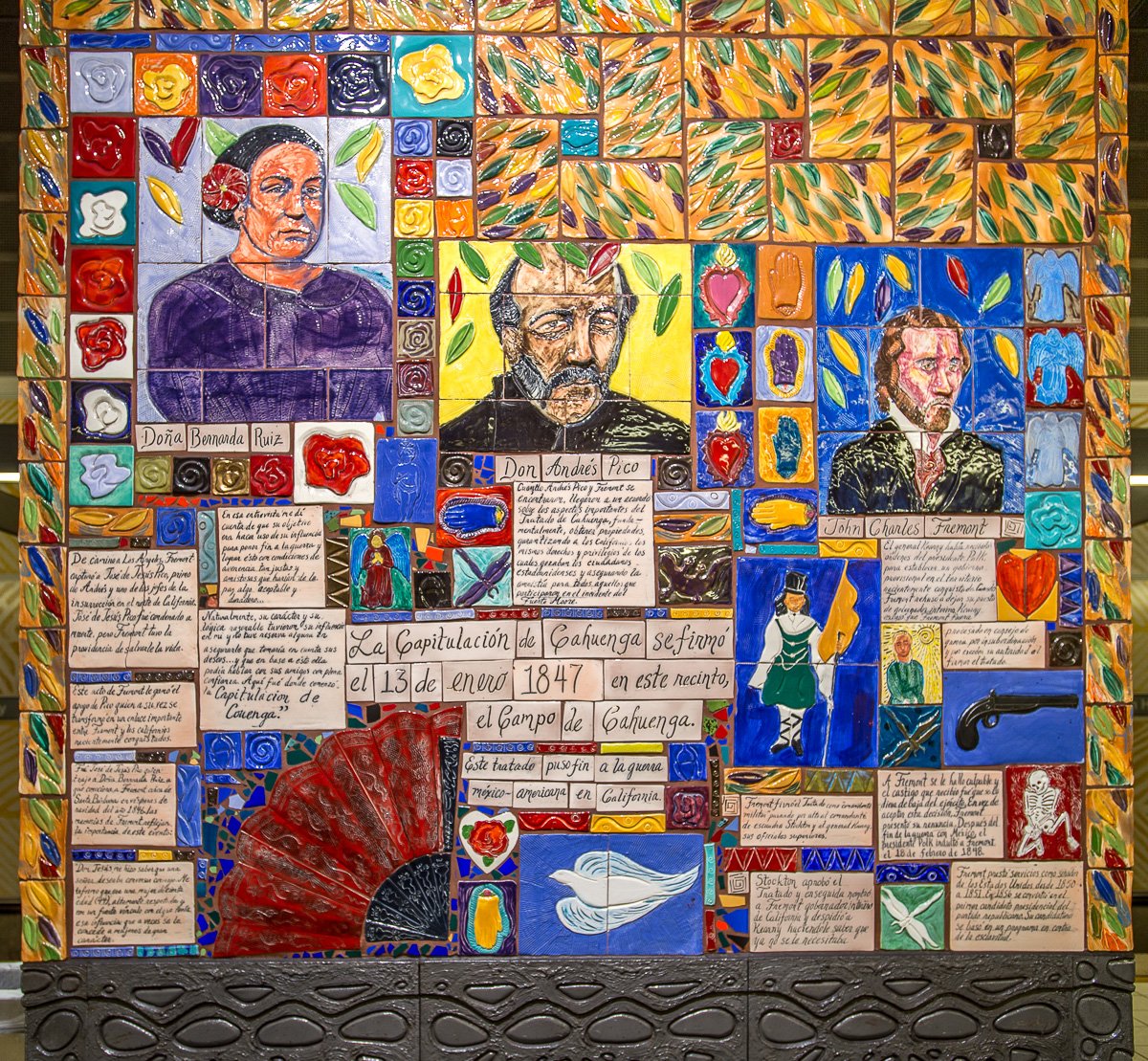

Each tree trunk is clad in handmade colorful art tiles that reflect the history of the area and its people, and offers a visual and textual narrative of the events leading up to the Capitulation of Cahuenga. The Mayan letter “G” appears as a consistent design element throughout the station, in screened porcelain wall panels, cast iron railings, wainscoting and benches, and on the elevator glass, and symbolizes all beginnings and endings. The artist and architect have titled the project The Trees of Califa. “This station is situated on a sacred site…sacred because of its history. Our history. The work here is meant to honor that.”

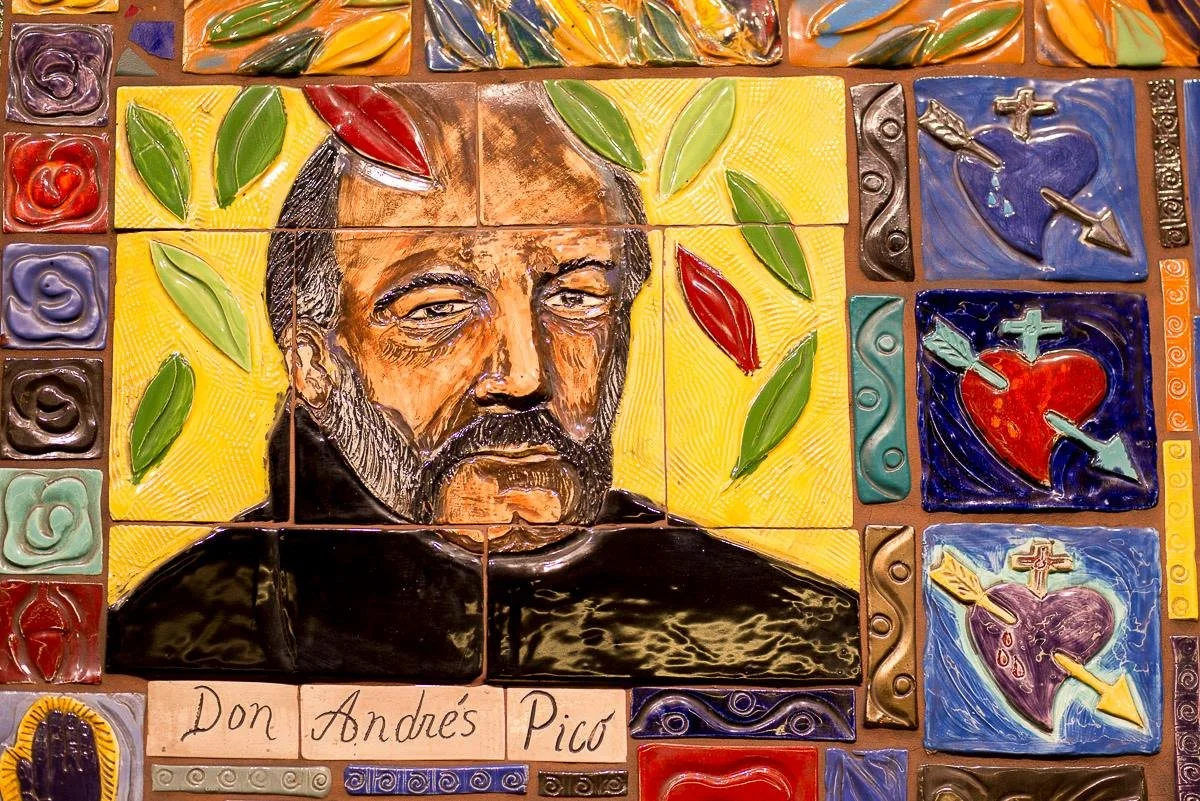

Ceramic Tile Installation at platform level.

Introduction

On the platform level of the station are four columns covered with ceramic tile. Each column, from the floor to the lights, stands approximately 16 feet high and is 3 feet by 8 feet wide. The tile on the columns reflects the history of the Campo leading up to the signing of the capitulation.

The following is the story, written in both English and Spanish, since the Capitulation of Cahuenga was also written in these two languages. Included are some of the leading figures of this story. Also present are symbols such as the acorn which was a staple in the Gabrielino diet, as well as the datura blossom which was used in their religious ceremonies.

When the area now known as California was first heard of by Hernan Cortez, the conqueror of Mexico, it has just been named by his lieutenants for an imaginary figure from a fanciful romance of the era: Las Sergas de Esplandian (1510) by Garci Rodriguez Ordonez de Montalvo. In that book, a Queen Califa was said to rule a tribe of black Amazon warriors in a fabulous land that abounded in pearls and griffins and was presumed to be situated in the Great South Sea “very near the Terrestrial paradise”.

Although the Queen was never found, perhaps her spirit was. In her name, this work is titled “The Trees of Queen Califa”.

Artist Statement, Margaret Garcia, Artist, 2000

“The work at the station depicts an important time in American History. It is a time when California went through a transition that helped form the nature of United State’ role in foreign affairs. The acquisition of the Bay of San Francisco facilitated trade with China and led to the “Boxer Rebellion”.

When studying the war between the United States and Mexico, Texas has always viewed as the Golden Fleece but evidence is available to question that motive. The prize was grander than first realized. United States grew by half (1846-1848). Mexico on the other hand, lost half its territory.

Much history is debated and I am sure that this history will continue to be so. However, with the help of Bill Mason [veteran historian and longtime curator of Southern California history at the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History] I have made an effort to present the events as they took place leading up to the signing of the “Capitulation of Cahuenga.”

As a Chicana I suffer the duality of many people who are bicultural suffer. As an American citizen I am proud of my Mexican heritage. It is an effort on my part to credit those people who struggled to protect the rights and freedom of so many. It certainly took a large degree of courage on the part of John C. Fremont to sign as well as Andres Pico and those who waged the battles to defend the citizens of Los Angeles. The signing of the Capitulation set in motion policies that we are still trying to understand.

For Mexicans who live and lived here it has meant that their history though not forgotten has certainly been ignored.

The idea that history will repeat itself unless we learn those all-important lessons should not be lost here. Campo de Cahuenga is a place where two cultures came together to find peace”.

The Story of how California was taken from Mexico by U.S. armed forces, leading to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo 1847

Column 1: Native-American through the Mission-Rancho period.

“Native Americans had lived in California for over 10,000 years when Gaspar de Portola arrived in 1769. With the Portola Expedition came Father Junipero Serra who established the Catholic mission system. Although occasional tribal warfare occurred during food shortages, the Gabrielino Indians were a gentle people, especially in the handling of their children. The Padres complained that they “treated their children like idols” because the children lacked discipline.

This permissive attitude contrasted sharply with the discipline imposed by Padres in running the missions. For example, once an Indian decided to join a mission, he was not permitted to leave. If he left and failed to return, he could be hunted down, beaten, or even killed. Furthermore, Indians were denied specific privileges, such as riding horses or using European weapons.

Indians were not considered “gente de razón” (people capable of reason). They were viewed as children. Though the Padres were charged with training them in skilled labor and educating them in preparation for self-government, they were seldom taught to read.

California, which had the largest Native American population in what is now the U.S., became a place where many tribes disappeared. European diseases such as smallpox spread through the living quarters of overcrowded missions. Indians were no longer permitted to practice their religious and ceremonial bathing. This spawned further disease. Under such unhygienic conditions, infant mortality rose. The final blow to the Indians came in 1849 when gold was discovered in California. What remained of the Indian culture was nearly destroyed by the arrival of thousands of lawless gold-seekers known as the “forty-niners.”

The church acted as guardian, holding mission property until the day Indians would be self-governing. Settlers from Mexico saw it in their own best interest to dismantle the mission system so they could appropriate the hotly contested lands.

There were many Indians whom the Padres still wanted to baptize when the Mexican settlers moved in. The Padres protested that the townspeople were taking advantage of these natives. At times, they would labor for an entire week and only be paid a lace handkerchief or a bottle of alcohol. Women could be taken advantage of, then abandoned. Men who did this were at times publicly punished.

Pío Pico, Governor of California, and Andrés Pico, Commander of the Californio forces, were brothers and Mexican of African descent.

In California, even more than in the rest of Mexico, a person’s station in life was not strictly determined by race, but by his or her cultural assimilation and attainment of education. An Indian who wore the trappings of a well-educated person could assume a higher social status.

Many Californios spoke the local Gabrielino language because they were accustomed to negotiating with the Indians.

Forty-four persons from northwestern Mexico founded the City of Los Angeles. More than half were of African descent. This era has been referred to as California’s Spanish Period because Spain ruled Mexico during this time and that rule extended to California. However, California was settled by Mexicans, not Spaniards. Of those who claimed Spanish descent, half intermarried with mestizo, Indian, or people of African descent. Only one to three percent were actually from Spain.

Many residents defined themselves as “Californios.” This was not meant to deny their Mexican heritage, but to assert their love for their most beloved California.

During the Mexican American War from 1846-48, the population of California numbered approximately 7,000 Mexicans; 15,000 mission Indians and non-baptized Indians conversant with the Mexican culture; and 1,000 foreigners who were a mixture of other Latin Americans, European and U.S. immigrants”.

Column 2: Leading to War

“ ‘As to Texas, I regard it as of but little value compared with California—the richest, the most beautiful, the healthiest country in the world. The harbor of St. [San] Francisco is capacious enough to receive the navies of all the world, and the neighborhood furnishes live oak enough to build all the ships of those navies!'’ Message to President John Tyler from Waddy Thompson, United States representative to Mexico, 1841-1845. On October 20, 1842, Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones, Commander of U.S. naval forces, seized Monterey Bay in California.

This was the first evidence of U.S. intentions to include Mexico as part of the westward expansion. Embarrassed to discover that no war had been declared, Jones apologized to then California Governor Manuel Micheltorena and departed.

By the mid-1840s the primary U.S. military concern was the dispute with Mexico over the location of the Texas border. James Polk was elected President in 1844 on an expansionist platform. He made it clear that a war with Mexico was inevitable

As early as 1845, U.S. Commodore J. D. Sloat was stationed off the coast of Mexico and California. As Commander of the Pacific Fleet, his instructions were to seize San Francisco should war between Mexico and the United States break out. When Congress declared war on Mexico May 13, 1846, Sloat’s orders were enlarged to include the capture of Monterey.

Sloat Came ashore July 7, 1846 to formally claim California for the United States. The proclamation promised respect for the rights of the individual, including religious freedom. Later when Sloat became ill, he transferred command to Commodore Robert F. Stockton.

Military explorer John Charles Fremont, also known as “The Pathfinder,” had led two surveying parties into California from 1844-46. The Mexicans distrusted him because he traveled armed with a small cannon and his party was made up of U.S. soldiers. In March of 1846, he was ordered to leave by the Mexican government, but instead Fremont raised the U.S. flag over Hawks’ Peak, 25 miles from Monterey. He began to build a fort but then withdrew to Oregon. However, his action set the stage for the next overt act of U.S. aggression.

In June of 1846, a band of U.S. citizens took over Mexican headquarters at Sonoma, in northern California. They seized the town and raised a homemade flag bearing a single star, a grizzly bear, and the words “California Republic.” This act has come to be known as the “Bear Flag Revolt.”

James K. Polk was elected President in 1844 on an expansionist platform. He made it clear that a war with Mexico was inevitable.

Word spread throughout California that the U.S. was at war with Mexico. Fremont returned to California where he joined Commodore Stockton, who promoted Fremont to Lieutenant Colonel.

Stockton threatened the citizens with dire punishment should they fail to cooperate with the new government. U.S. soldiers and marines marched south, finally taking Los Angeles, the capital of California, August 13, 1846. California Governor Pío Pico fled to Mexico rather than surrender.

Stockton left agent Archibald Gillespie with 50 men to garrison Los Angeles. This nearly proved a catastrophe. A local citizen, Servulo Varelas, along with several friends, fired their muskets in the plaza, shouting “Viva México!” In the night, Gillespie and his men fired a few shots in the direction of the disturbance, which had attracted a number of onlookers. At least one man was wounded. The following day, Gillespie arrested a number of paroled Mexican officers, believing them responsible for the skirmish. This united public opinion against the U.S. troops and Gillespie and his forces were besieged at Fort Moore.

Gillespie and his men bargained for their release from the siege, which was granted on condition that they leave their cannons behind on the beach at San Pedro. Don Andrés Pico, Commander of the Californio forces, accepted the cannons only to discover that they had been spiked and rendered useless.”

Column 3: War

“The following day, Gillespie arrested a number of paroled Mexican officers, believing them responsible for the skirmish. This united public opinion against the U.S. troops and Gillespie and his forces were besieged at Fort Moore.

Gillespie and his men bargained for their release from the siege, which was granted on condition that they leave their cannons behind on the beach at San Pedro. Don Andrés Pico, Commander of the Californio forces, accepted the cannons only to discover that they had been spiked and rendered useless.”

“Andrés Pico and 100 men were the principal defenders of southern California. They had few firearms and relied on homemade gunpowder made by a one-eyed man named Francisco Rico. They knew U.S. forces would return to try to take back Los Angeles.

Andrés Pico and his men unearthed a small bronze cannon they had entrusted to Inocencia Reyes, an older woman whose servants had hidden it in her garden. They cleaned it, placed it on a “carreta” as a gun carriage, and prepared to defend Los Angeles.

Gillespie and navy Captain William Mervine returned to retake Los Angeles, their forces had few horses and proved no match for the cannon. This victory is called “The Battle of the Old Woman’s Gun at Rancho Dominguez.” Gillespie and Mervine withdrew and sailed south to San Diego where they rejoined Commodore Stockton.

U.S. forces sent scout Kit Carson to find General Stephen W. Kearny in New Mexico where he was preparing to invade California. Unaware of the recent losses in Los Angeles, Carson misinformed Kearny that a complete conquest had occurred. With Carson as guide, Kearny trekked 1000 miles to California with only a portion of his force, leaving over half his men to help garrison New Mexico. When he arrived, he discovered that the Californios had rebelled against U.S. occupation forces.

At San Pascual, Andrés Pico and his men lay in wait for Kearny. Kearny’s forces attacked on December 6, 1846, just before dawn. A cold mist and fog shrouded the battlefield. Their gunpowder was wet and their guns would not fire. Kearny’s brigade proved no match for the excellent horsemanship of Andrés Pico’s men and their long lances. They easily defeated Kearny’s forces. Kearny’s losses were: 21 dead, 18 wounded; Pico’s casualties were two dead, 18 wounded”.

Column 4: Peace - The Capitulation of Cahuenga

“Meanwhile, Fremont had also been busy. Having recruited nearly 400 men from central and northern California, he too headed toward Los Angeles. He made contact with the enemy field forces outside the city on January 12, 1847, just two days after Stockton had retaken Los Angeles.

On his way to Los Angeles, Fremont captured José de Jesús Pico, Andrés Pico’s cousin and a leader of the insurrection in northern California. José de Jesús Pico was sentenced to death, but Fremont had the foresight to spare his life. This act by Fremont won Pico over; he in turn became an important liaison between Fremont and the newly-conquered Californios.

It was José de Jesús Pico who brought Doña Bernarda Ruiz to meet Fremont near Santa Barbara on Christmas Eve, 1846. Fremont’s memoirs note the importance of this event:

“Don Jesús brought me word that a lady wished to confer with me. He informed me that she was a woman of some age, highly respected and having a strong connection, over which she had the influence sometimes accorded to women of high character.

In the interview I found that her object was to use her influence to put an end to the war, and to do so upon such just and friendly terms of compromise as would make the peace acceptable and enduring...

...Naturally, her character and sound reasoning had its influence with me, and I had no reserves when I assured her that I would bear her wishes in mind...and that she might with all confidence speak on this basis with her friends. Here began the CAPITULATION OF COUENGA.”

When Andrés Pico and Fremont met, they agreed to important features of the Treaty of Cahuenga, primarily securing property, guaranteeing Californios the same rights and privileges enjoyed by U.S. citizens, and assuring amnesty for those who had participated in the incident at Fort Moore.

Doña Bernada Ruiz, Don Andreas Pico and John Charles Fremont

Doña Bernada Ruiz